All Your iCloud Accounts Are Belong To Us

When a group calling themselves “The Turkish Crime Family” threatens to wipe hundreds of millions of Apple devices unless they’re paid a bizarrely small amount of money by April 7th, 2017, what do you do? If you’re Apple, you give the offenders a corporate-speak version of the middle finger: we do “not reward cyber criminals for breaking the law.”

The exact details of the situation keep changing. Maybe it’s 300 hundred million accounts that have been compromised, maybe it’s 500 million, maybe it’s half that. The demands keep changing. The TCF wants $70,000‒which is a pittance for a real threat to one of the world’s wealthiest companies. But wait, they really want a hundred thousand. And that’s per member of the TCF, not in total. And they want some other things from Apple that they’d like to keep private. But there’s little that’s private about this whole thing. Maybe that’s because the TCF are how they appear; like teenagers demanding attention, rather than a serious threat.

Regardless of how the saga eventually unfolds, one thing is clear: Your Apple iCloud account is you, online. It’s your photos, your contacts, your messages, your bookmarks, your browser history, your schedule, and your health and activity records. Synchronized invisibly between your Apple products, your iCloud account breaths life into your devices and makes them yours. Encrypted to keep everyone, including Apple, out of your stuff, your iCloud account is protected by your password, which this group claims to have.

If you’re only interested in what you can do to protect yourself against the threat, read the next two sections. If you’re interested in the bigger picture‒ what may have happened and what Apple can do about it‒check out the middle two sections. Or you can skip to the final section to see what’s likely to be the outcome.

What You Should Do, Part 1: Your Password

Your password is the first line of defense for your Apple iCloud account, and most other Internet accounts. Too simple a password is weak and easy to guess. A human trying to break into your account may be able to guess it, or software can quickly iterate over a list of simple common passwords (or even just the dictionary) to gain access. And if you use the same password on multiple web sites, you’re at risk too. When one site gets broken into and has its account information stolen, anyone with that information can then get into accounts on other sites that reuse the same passwords, or subtle variations of the same passwords.

Ideally, your iCloud account password is long, includes numbers, both upper and lowercase letters, as well as punctuation. It shouldn’t be based on real words and shouldn’t be in use with any other online service.

“Ilovemydog” is not a good password. And “1l0v3myd0g” is not much better. Such simple substitutions are easy to predict. “asjeU4BvXbRFarz/3E” is way better. But very few people are willing or able to remember passwords like this. So rather than shrugging your shoulders and keeping “Houston78” as your easily bypassable password, use a reputable password manager like 1Password to generate and store strong passwords.

You can change your iCloud account password on a trusted device by using the Settings app, going to the iCloud section and then tapping on your account. Or you can change it via the web at https://appleid.apple.com/

If you do change your password, expect to have to update each of your devices that is logged into the iTunes Store on that account, possibly multiple times.

If you use a password manager that syncs via iCloud, iCloud syncing may be paused until you let your device know your new password. You might want to choose the password and make sure your password manager has synced before changing it, or be prepared to type or tap it in to your device directly.

While passwords are ubiquitous, they’re also easy to compromise. Anyone who knows your password can access your account. If everyone used difficult to guess passwords and remembered and managed them perfectly, that alone might be sufficient to keep everybody secure. But that’s just not real life, so we need a second layer of protection.

What You Should Do, Part 2: Two-Factor Authentication

Two-factor authentication (2FA for short) does exactly what it says. It adds a second “factor” to your login process. Providing your password gets you the chance to use this second factor in order to login. The second factor usually involves a physical object that you’ll have in your possession: your phone, a USB key, a trusted device which you can use to say “yup, this is really me”.

Adding an extra factor means an attacker needs not one, but two things to login. So even if I posted my email address and password on a billboard, no one could access my account without having a certain device in their possession. (Although I would likely be bombarded by 2FA requests for verification.) And often the device providing the second factor is itself protected by a verification code or fingerprint.

So 2FA, at the cost of just a few seconds to your login time, adds an immense amount of security to the process.

Apple’s own 2FA implementation requires a second validation from a trusted device‒another Apple device ‒or it can be a cell phone receiving a text message. You can only use 2FA if you’re running iOS 9 or later, or macOS El Capitan 10.11 or later.

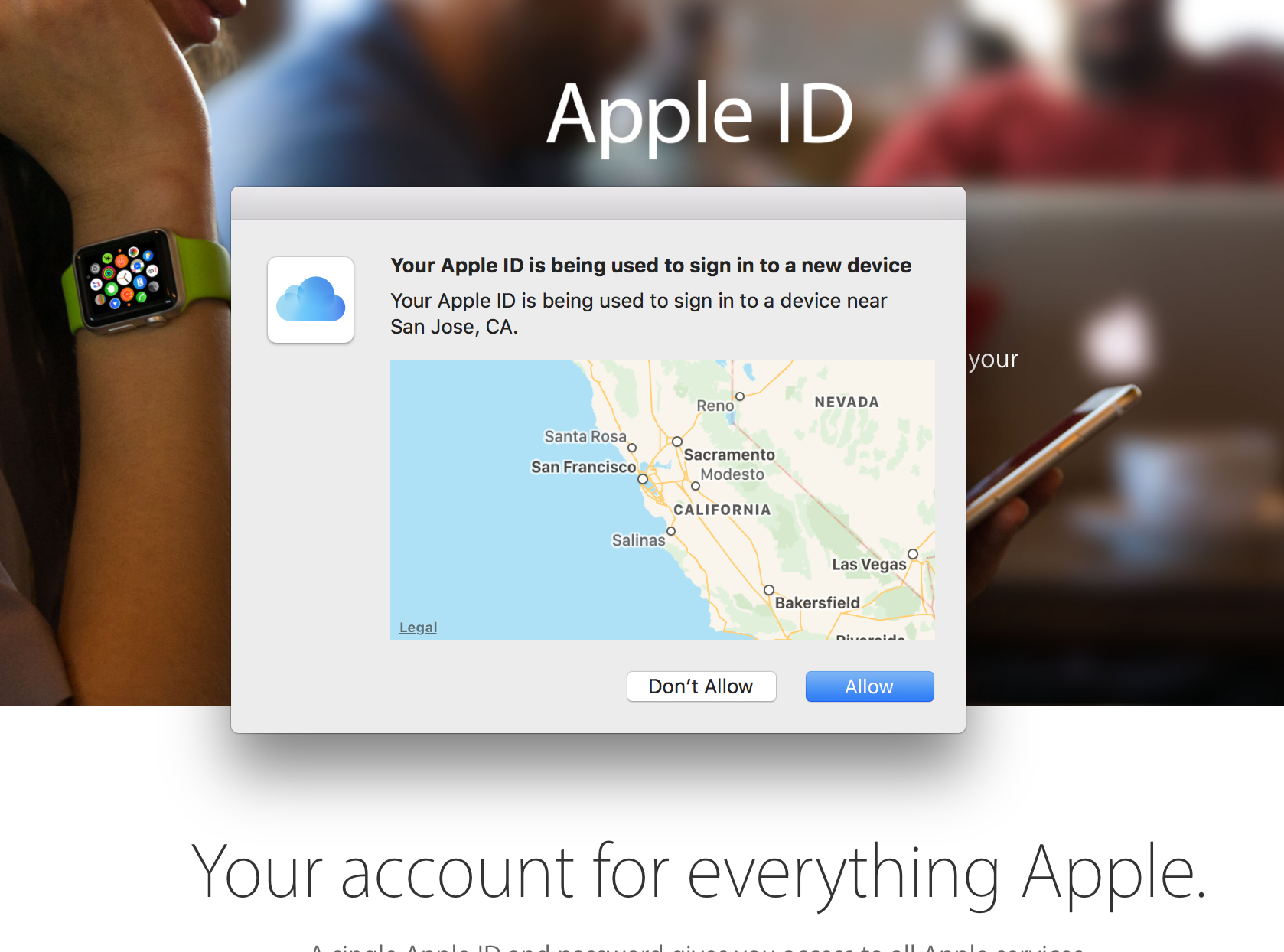

Once 2FA is enabled, when you login on a new device or web browser, expect to see two dialogs on your already trusted Apple devices. First, you’ll see a pop-up showing the requester’s location and asking you whether you want to allow or not.

If you ever see this pop-up and you’re not logging into a device or using a web browser with your Apple ID, click “Don’t Allow”.

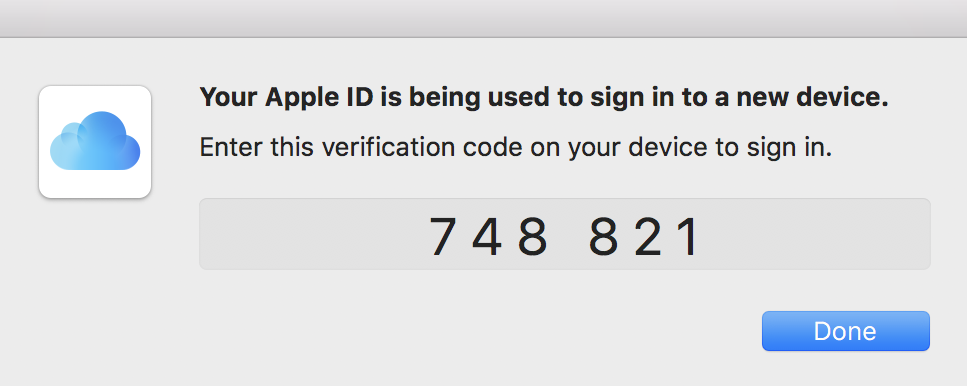

Next you’ll see a pop-up giving you a six digit verification number. You’ll need to enter this number on the device or web browser you’re trying to login on.

Even after you tell Apple to trust a device, you’ll go through this process again if you use your Apple ID on a web browser on that device. Which leads to funny looking situations where your browser is asking for 2FA information and the 2FA information is popping up over it on the same computer. Don’t worry, this is perfectly normal. Apple’s just making sure that it’s okay to trust the web browser, separately from trusting the computer.

If you can’t use two-factor authentication‒because you haven’t got the latest iOS or MacOS versions‒you can simply turn on “two-step verification”. This is a predecessor to Apple’s two-factor authentication. It uses SMS text messaging to send you a verification code that you’ll enter any time you login using your Apple ID on a new device or web browser. Definitely use 2FA if you can; if you can’t, two-step verification is your fallback.

TCF vs Apple: What Might Have Happened

Apple is denying the TCFs statements and says that their systems haven’t been compromised. While I have no direct knowledge of Apple’s internal security, I’m inclined to believe them. We’re talking about hundreds of millions of account records here. If Apple has reasonable security‒and I think it’s reasonable to expect that their security is echelons above reasonable‒they would notice, or at least have a record of, transfers that large.

However, the group has demonstrated that they can access 54 of the accounts. They’re clearly not just making the entire thing up.

Apple suggested that the credentials may have come from compromised third party databases, and it appears that the hacking group agrees. Many people use the same email address and password on multiple websites and services; when one of those sites is cracked and its user database is read, accounts with re-used passwords are in danger on other sites.

But if you’re using a strong and unique password on your Apple ID, you should be safe. Turn on 2FA or two-step verification and you’ll be even safer.

TCF vs Apple: What Can Apple Do?

Whatever the TCF plans to do to the set of accounts they have credentials for, be it wiping, resetting, or publicizing, it’s not something they can easily or quickly do to hundreds of millions of accounts. It takes time and resources.

But the hacking group has published details of how it plans to attack, including how many accounts per second they can wipe per server they’ll be attacking from. If what they say is true, it will look like a distributed denial of service attack on Apple’s servers; the servers will be flooded by requests coming in from multiple computers. But Apple likely deals with DDOS attacks on its servers every day. So it’s possible that Apple’s existing defenses might handily prevent most of the attack. If not, it’s easy for Apple to add defenses that disallow multiple rapid account resets from the same IP address. A few initial resets might get through before the defenses would trigger, but the bulk of them would be blocked.

We also have no idea of how many of these hundreds of millions of iCloud account credentials can be used to access iCloud. The group indicates that they all can, but I’m doubtful they could have verified them all without Apple noticing and blocking them in the process. However, they have demonstrated that at least a few of them work to get access. But that’s hardly surprising given how terrible people are with passwords.

If there is a path into iCloud’s services that somehow accepts old passwords and bypasses 2FA and two-step verification, then Apple has a big problem on their hands. But this seems very unlikely‒Apple is highly motivated to review all paths into iCloud, and as of late 2016 they have a bug bounty program, so outsiders are motivated to find and disclose vulnerabilities as well.

Outcomes

It’s possible that nothing will happen. The group may be physically prevented from attacking or may simply not attack. Or Apple may completely foil it. I doubt that any of these outcomes are likely.

But assuming the group goes ahead with its attack on April 7th, Apple will already have defenses in place to block the attack.

The attackers almost certainly do have some number of valid iCloud logins, simply because humans are horrible at managing passwords‒but not hundreds of millions. And Apple’s defenses will almost certainly mitigate much of the attack.

The most likely outcomes are a relatively small number of accounts compromised and reset (not hundreds of millions), and possibly degraded service from Apple due to the high levels of traffic their servers will be fielding. This is something anyone could accomplish on any day without any fanfare.

The unlikely, worst case scenario is the group somehow gets through Apple’s defenses and does reset a high number of accounts. They could lock people out of their iCloud accounts, remotely wipe their devices or tamper with settings and data.

***

This situation is a potential trainwreck. And though it may be fun to rubberneck and see whether it’s Apple or the TCF that comes off worse, you need to make sure you’re not caught in the middle of such an easily avoidable crash. Set up a strong password that’s unique to Apple, and enable 2FA or two-step verification, and you’ll be safe.

Although, it’s worth saying, this is something you should already be doing, regardless of the exploits of Turkish Crime Family.